See also:- 1) an article on Engels in Eastbourne website, Brighton University: “The International Workers’ Mural that Eastbourne Should Not Forget”; 2) video for laptop of the mural; 3) video for mobile phone of the mural.

Prologue

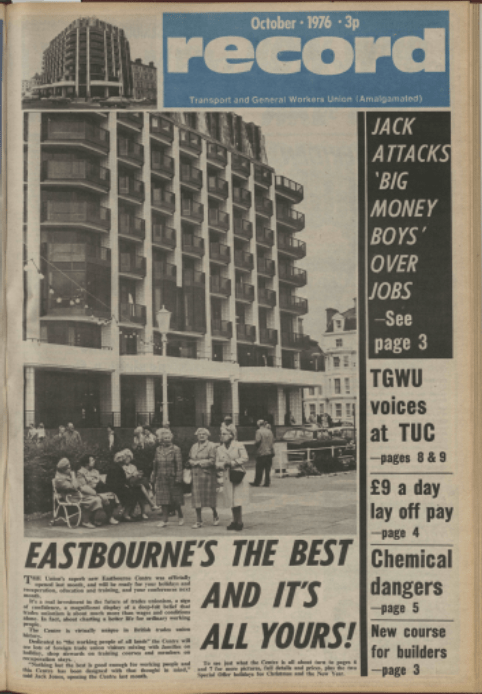

The 27.16 x 1.1m (89’1″ x 3’7″) frieze, known as Eastbourne’s “International Workers Mural” was painted by an art workers’ co-operative in 1976. Mick Jones, Christopher Robinson, and Simon Barber created it as a site specific installation for the dining area balcony overlooking the reception and restaurant of the Eastbourne Centre, which opened in September that year. The Centre was built by the

Transport and General Workers Union (TGWU) for “the working people of all lands” to use as a holiday & recuperation, education & training, and conference centre. Mick Jones, who trained at the Royal College of Art, was the son of the TGWU leader Jack Jones.

The frieze features Eastbourne and the South Downs prominently; from the first impressionistic panel directly referencing the peasant figure poses of Van Gogh, to the last, of a working man at rest looking out to sea and the Seven Sisters. The frieze’s original title, “The Forward March of Labour” reflects its depiction of the history of labour and the achievements and aspirations of the Union.

Fourteen panels run in chronological order from left to right, forming a single narrative paying artistic tribute to international Trade Unionism and the solidarity amongst workers. Examples abound, including; “the union’s struggle through depression and war, from which emerges a victorious procession with banners of the amalgamated unions”, and 1930’s support for the Spanish Republic referenced by the inclusion of the “SOLIDARITY WITH SPAIN” graffiti. Mick’s father, Jack Jones, was shot in the shoulder serving as a political commissar with the British Battalion of the XV International Brigade (Major Attlee Company), fighting against the fascists in the Spanish Civil War.

This post retains the original 1970s panel descriptions devised by the artist Mick Jones, and the Eastbourne Centre’s first manager, Alan Simpson. The historical language is of its time, and is not intended to offend.

Contents

The Perennial Innocence of Labour (Panel 1)

At the start of the mural we see the early morning sunrise over the sea and the English coast behind the archetypal figure of the ‘Sower’ walking out, strewing his seed from behind a blackthorn bush. He is the perennial innocence of Labour, man’s closeness to the earth and co-operation with the seasons which has been for all time. Birds fly up, a rabbit peeps out, birds sing in the holly and ivy amidst fruit. Here also the ‘Reaper’ swings his heavy scythe flashing in the sun with the symbolism of time.

The Industrial Revolution (Panel 2)

Across a stream, the advent of the ‘Industrial Revolution’ and ‘Class System’ is shown with a headless aristocrat on his horse with a key in his back. But who will keep winding it up? Behind, a jobless worker holds out his hand. The horse is the mute spectator of the oppression of capital shown in two large downtrodden figures heaving a coal cart, behind which, an explosion riddled with curious faces brings the coal tumbling down and rips open the sky revealing night.

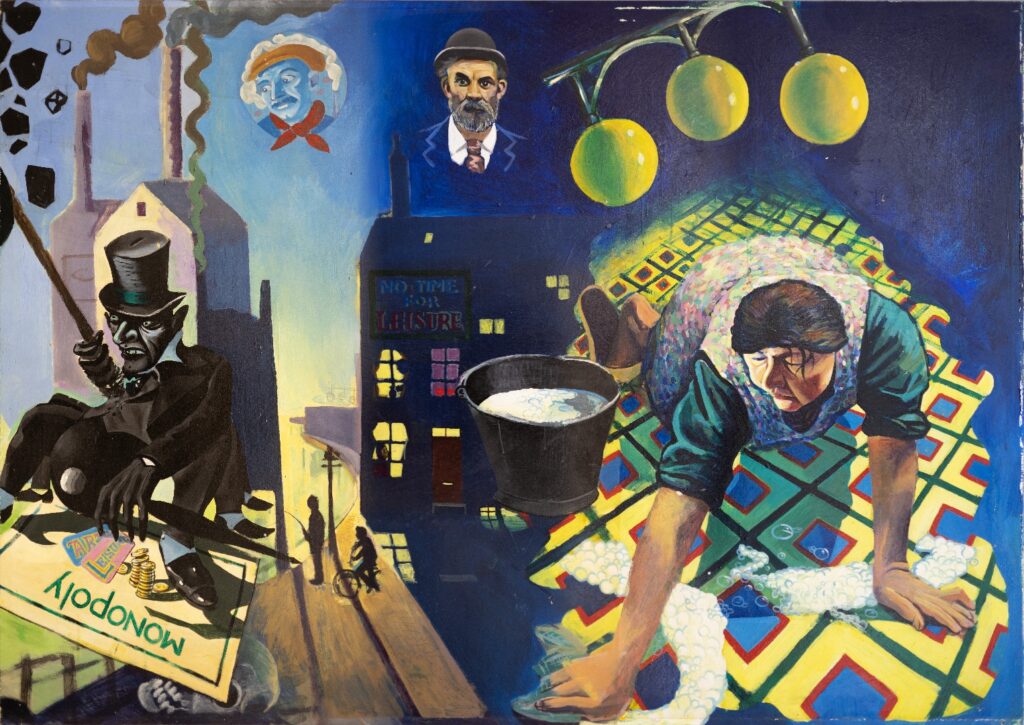

No Time for Leisure (Panel 3)

A top-hatted figure with the many legs of a spider pulls the rope. He sits over a Monopoly Board holding the cards of ‘Art’ and Leisure’. Underneath is a skull, and behind in the sky the red-kerchiefed spirit of a workman gazes down over an industrial landscape. Over a darkened house with the sign ‘No time for Leisure’, John Burns the Union Leader looks out. A large figure of an old charlady follows at her never-ending task of scrubbing the floor with a real scrubbing brush beneath the three balls of the ever-present pawnbroker’s sign.

The Call to UNITE (Panel 4)

The call to UNITE comes out of a blue void where water meets sky. Here stands the figure of Keir Hardie and opposite the head of Karl Marx. Above the young Tom Mann, Ben Tillet in characteristic Stetson makes the call, and above the illuminated letters rises the spirit of union, red roses in her hair. The other figures of different ages and races swirl in the void, a duck floats on the water.

The General Strike and Unemployment (Panel 5)

A series of brick arches follows, daubed with the political slogans typically of the period from General Strike to the war years. In the first, a washerwoman steps out of the void hanging up a red garment to dry. Behind her, the figure of Ernest Bevin defiantly leans over a line of poor back-to-back houses. On a roof in the foreground a black cat tears the heart from a bird, symbolising the period of struggle. In the next arch, a crying child is trapped behind the turning wheels of industry, a suffragette is chained to railings. Two early coachbuilders, one clutching his axe, both tool and weapon, and the other holding a heavy wheel over his heart, stand determinedly above struggling demonstrators fighting with point-eared police. The red flag is torn from the battling woman protestors.

In the next arch, the classic figure of the unemployed man taken from a famous photograph stands leaning dejectedly against the wall. A fanged Hitler ominously raises his hand in fascist salute, under storm clouds over swastika banners and columns of marching soldiers, behind him two capitalists, one blue and be-monocled, the other pig-like. Below, are the proudly marching Jarrow hunger marchers going the opposite way, and in the foreground, the tortured concentration camp prisoner clutches his bowed head. A line of lamps runs out through the arch, symbolising progress even through oppression.

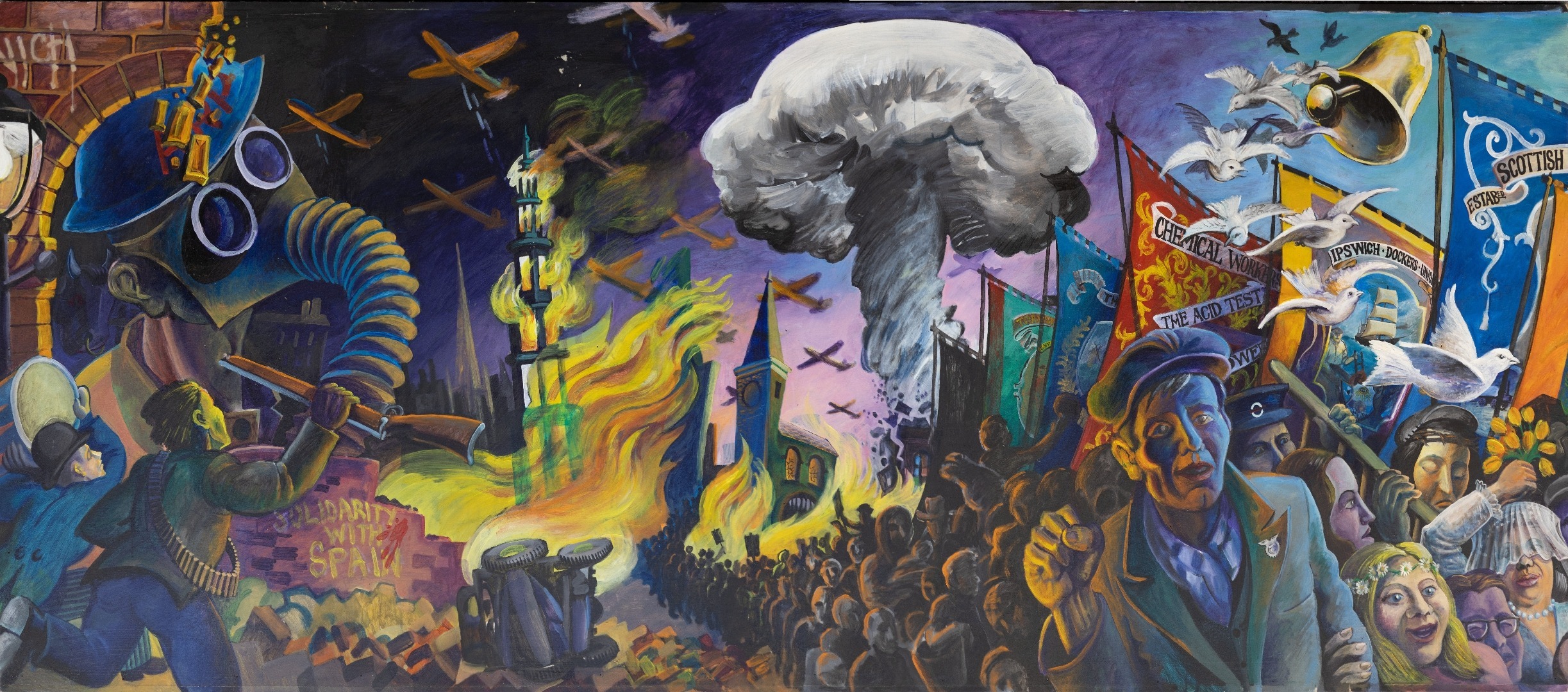

The War (Panel 6)

The war. This time is depicted by civilian fighters running into battle, one bearing his rifle aloft, the other carrying a symbolic drum. Behind, the arch crashed down and a huge gas-masked figure of an air raid warden reminiscent of an elephant looms out blindly staring at the darkened sky filled with bombers. A bull stands behind. Bombs rain on a burning town, a church tower blazes behind an overturned burning car. Another church screams in the flames. The atom bomb explodes and under its mushroom shadow, a peoples’ march straggles out between the flames.

Union and Peace: The Spirit of Liberty (Panel 7)

This march becomes a Union procession with the old banners of many of the Unions amalgamated into the T G W U proudly borne aloft. A bell rings in the empty sky releasing a flight of peaceful doves. A working man marching

between light and dark resolutely clenches his fist beneath the chemical workers’ Acid Test banner. On his arm a young girl with a springtime daisy chain. In the crowd is a cloth-capped Christ helped with his ladder by a London Transport worker. There is a bride and groom, faces of all ages, a peace sign held aloft, West Indians lowing heartily, a smiling Indian, and at the termination, a large family group.In front of a famous T G W U banner, with spirit of Liberty, a laughing old lady holds a flower and with her an old man toasts the Union over the ocean. A working man embraces a woman with a child, and a black worker who

gestures with the child to an illuminated slogan over the Union symbol in a bright dawn sky over the sea.

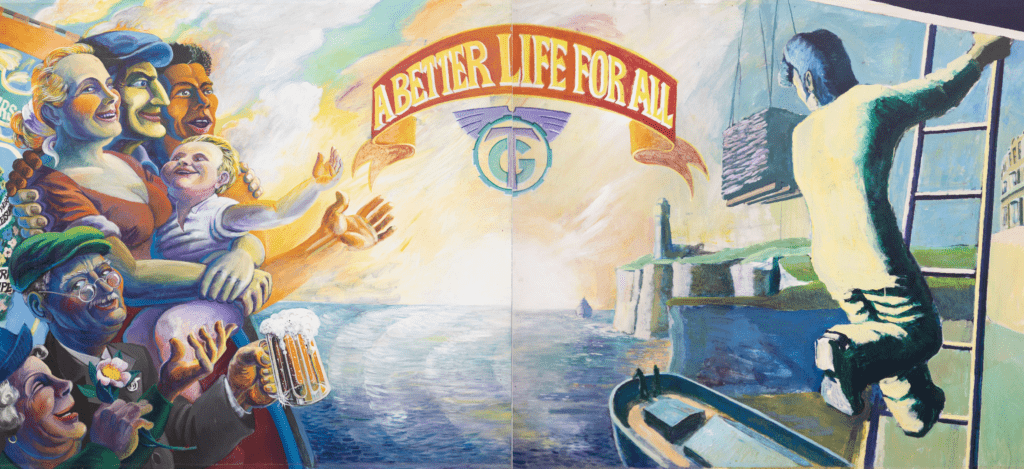

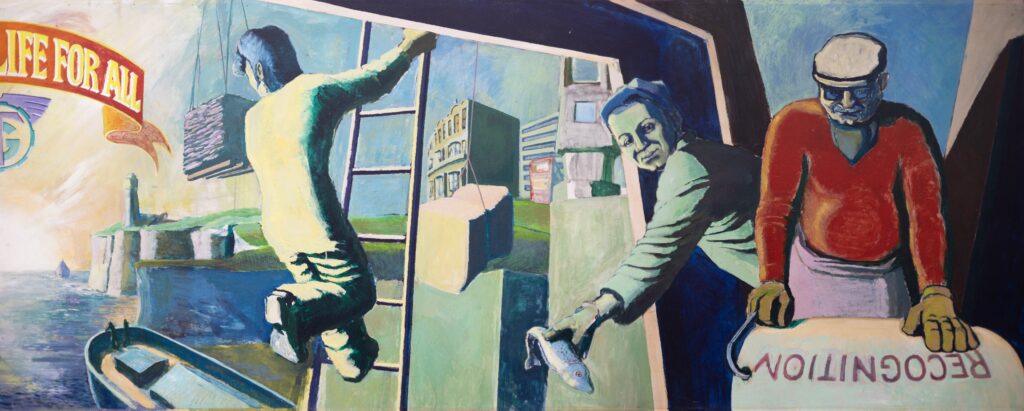

Recognition and Achievement (Panel 8)

Here, at the Centre of the mural, is as it were a second coming with the English coastline again, this time with symbolic lighthouse. In front of modern blocks of flats a workman climbs a ladder over a boat in the harbour. A fisherman proffers a fish to the spectator and a solid, red sweatered docker sticks his hook firmly in the bale of ‘Recognition’.

‘Modern’ Industry (Panel 9)

In this section on modern industry, some of the work and achievement of the Union is indicated. A modern industrial landscape is seen through the window of a factory. Here are factories, but by which trees are growing. In the street lorries are being loaded. A Pakistani worker helps his comrade swing the engine. In the factory it is still dark, men work the monotonous production line, but across the ceiling ‘Fair pay’ is writ large. A furnace man and a designer work side by side. Under a shining machine frill in the foreground, a West Indian woman worker controls her machine. In front of her, passes the bread and fruit of life, also a first-aid kit. A building worker above, working in the ceiling, passes down his pole.

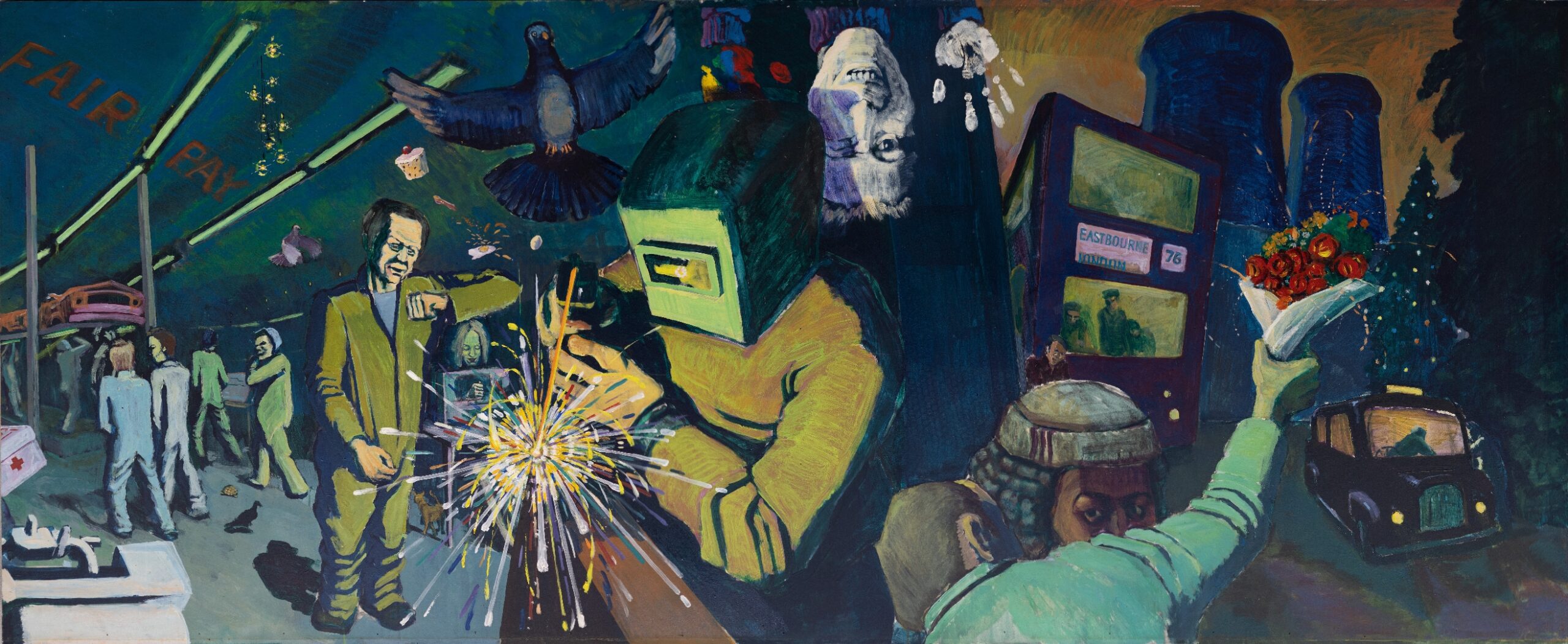

Workers (Panel 10)

A shop steward checks the time, the idea of refreshment visibly present in his mind. Other workers go for their tea-break in the factory canteen. A pigeon flies up behind the large safety-masked figure of a welder welding the unbreakable bond of union, his flame a mandala of rainbow colours. Behind him, a laughing upside-down figure lends some light relief to the scene. Out in the evening street, a man waiting with bus no. ’76. In front of an illuminated Christmas tree, a taxi is paid by its fare. Behind all, loom the huge cooling towers of the power station.

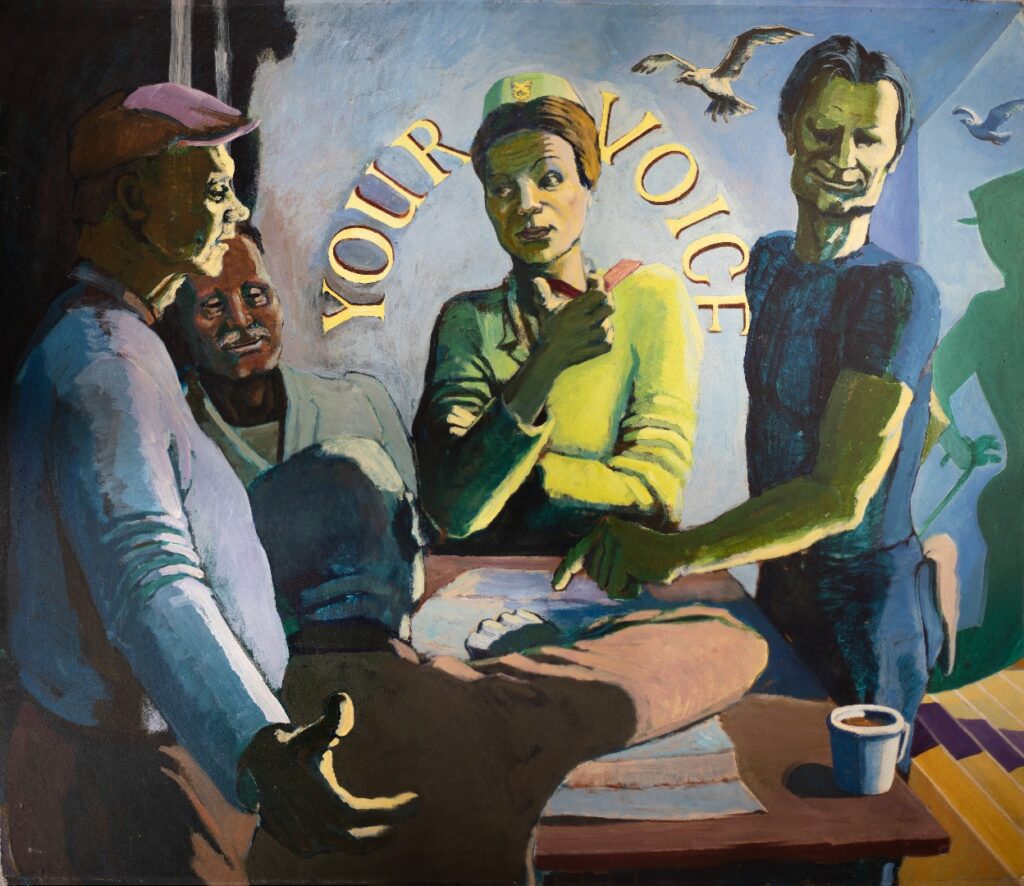

Union Meeting (Panel 11)

In the next corner a Union branch meeting is shown. Various members discuss points around a table. The Union “Maid” at Centre consults the rule book. Behind and ringing, her words “Your Voice”. A seagull flies in overhead bringing the message of Freedom. Stepping out down steps into the next section is the spirit of freedom as a green figure with hat and cane, a bird over his head.

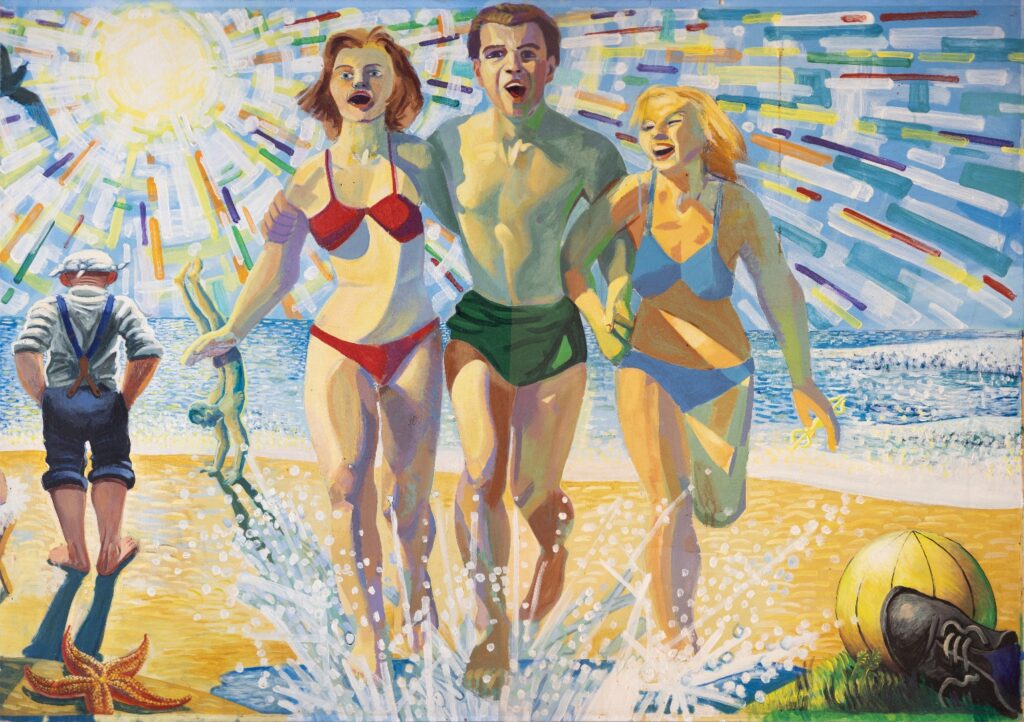

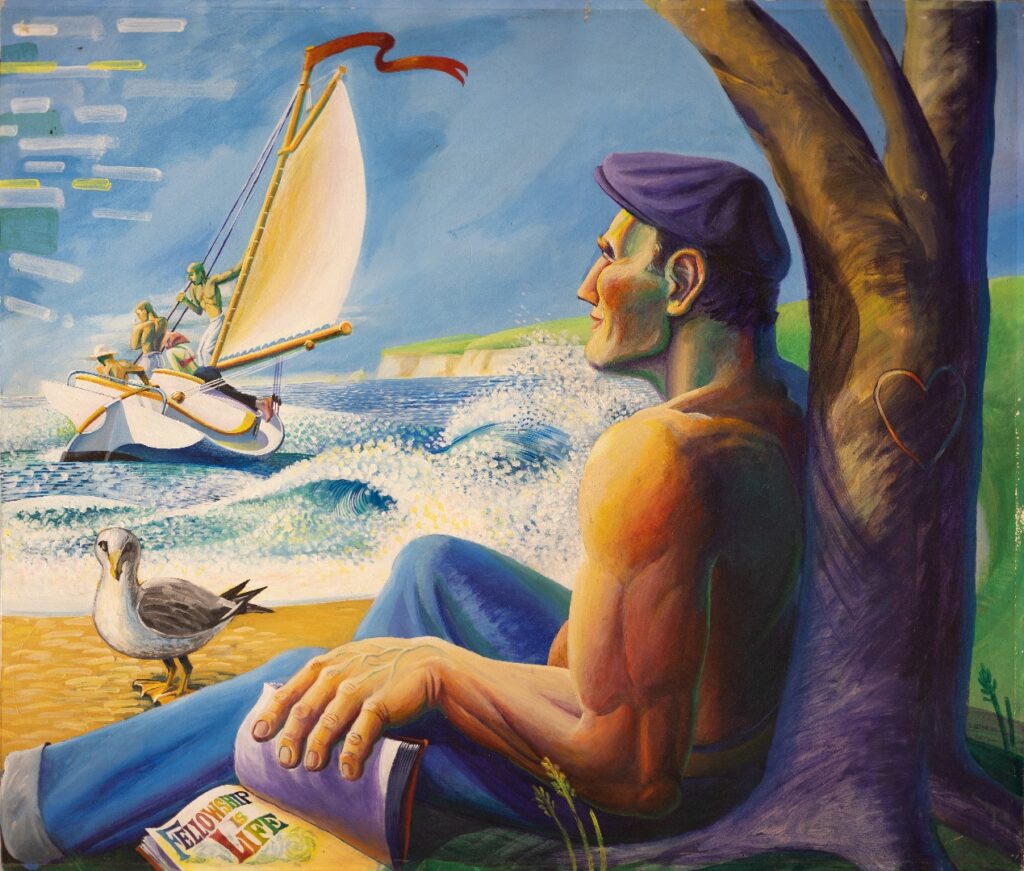

Art, Leisure, Freedom and Joy (Panels 12-14)

The last section is concerned with art, leisure, freedom, and joy. In the background is the Eastbourne Centre itself. A singer in front makes full use of his voice, at the same time painting a rainbow across the sky. A veiled dancer emerges from a clay pot being turned on a wheel, waving a red banner aloft over the building. She juggles with three gold balls, a far cry from the pawnbroker’s sign. Behind her, a saxophonist belts out his tune whilst his hand reaches to pick a flower from a rose bush in the foreground. Hands play a piano keyboard which is also the sea, from which a photographer emerges to snap a picture of us; and also a mother and a child with ice-cream, his head a blaze of golden hair in the sunlight. Above their heads, there is a postcard in the sky with a classic message. A bird flies up to the full bright sun of noon, filling the sky with a great splash of rainbow colours, echoed earlier in the

welder’s flame.

Beneath, on the beach stands the classic figure of the elderly working class man in his element on holiday, handkerchief on his head, trousers rolled up, he contemplates the ocean and casts a long shadow back to a red star fish in the foreground. A figure does a handstand and lifts his feet to the sun. Three laughing figures, a man with two girls, run forward out of the picture splashing joyfully through sunlit water.

A full-crewed yacht with banner aloft turns into the sun. And at the end, the strong figure of a working man at rest. In the sun, he leans his back against a tree carved with a heart. Cap firmly on, a large wave splashes behind him but appears to splash on his chest. He contemplates the scene looking back into the mural. At the foot, an atlas-like ball making an echo between the sun and the earth. His hand rests on a book with a rainbow lettered quote from William Morris, “Fellowship is life”. A seagull at rest standing on the beach, gazes out at the spectator.

Epilogue

overlooking the reception and

restaurant of the Eastbourne Centre

Mick Jones’ father Jack left school at 14, eventually joining Mick’s grandfather as a Liverpool Docker. Jack became an active member of the TGWU, and was converted to socialism by reading “The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists” by Robert Tressell. He once explained how that book “was passed from hand to hand among people in the Labour movement and had a remarkable effect on our thinking”. Influenced by William Morris, Tressell made art part of labour.

The TGWU was created in 1922 with Ernest Bevin as its first General Secretary. Jack Jones became General Secretary 1968-1978. Inspired by a visit to the Black Sea, and whilst attending a Labour Party Conference in Brighton, Jack searched the coast for a suitable location to build a Holiday & Recuperation, Education & Training, and Conference Centre. He found it in Eastbourne. After laying the first stone in 1974, Jack Jones returned in September 1976 to open The Eastbourne Centre, – “vitually unique in trades union history”. Jack said “Ernie Bevin had had a vision of a holiday centre for TGWU members on the south coast and I was able to help turn the dream into a reality”.

Although The Eastbourne Centre is now called The View Hotel, it is still owned by Unite the Union, the successor to the TGWU after its merger with Amicus. The balcony where the mural was displayed was removed in 2014 during refurbishments to launch The View Hotel for tourism. The new mezzanine still displays some of the hotel’s union history, but there has been nowhere to display the mural since its removal and storage in Birmingham.

The existence of Eastbourne’s International Workers’ Mural owes a lot to Jack Jones, his son Mick, and the other artists in the artist co-operative. Credit to Carol Mills and Matt Huddart from The View Hotel for keeping the Mural and its message alive. Acknowledgement also goes to Mark Metcalf, a researcher for Unite the Union. People’s Eastbourne aims to find a permanent in Eastbourne home for the mural.

Acknowledgements

The existence of Eastbourne’s International Workers Mural owes a lot to Jack Jones, his son Mick, and the art workers’ co-operative. Credit should be given to Carol Mills for keeping the Mural and its message alive, along with Matt Huddart from The View Hotel and Mark Metcalf, a Researcher for Unite the Union. The People’s Eastbourne Campaign aims to find a permanent Eastbourne home for the Mural.

Original text by Mick Jones and Alan Simpson.

Edited with prologue and epilogue by Carol Mills and Mike Munson.

All images of mural panels used with permission from The View Hotel / Unite the Union, all rights reserved.