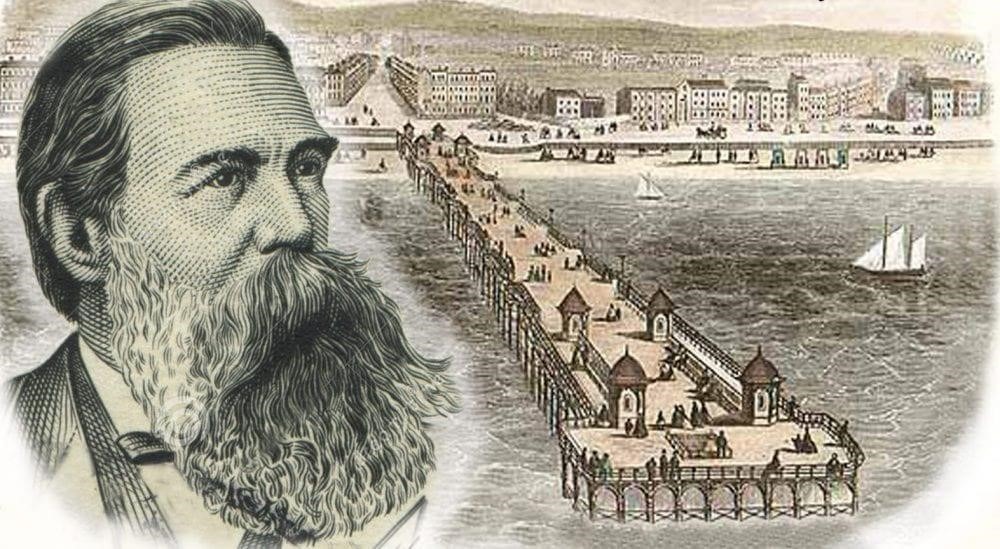

‘Engels in Eastbourne’, Nic Watts, Used with permission, all rights reserved

This Radical History Seafront Trail is taken from the fuller Radical History Tour.

Whether you are a visitor, or a resident of Eastbourne then welcome to this walk. The Radical History Seafront Trail starts at the Pier and proceeds along the seafront to the Western Lawns. The Trail was set up to celebrate and make visible some of Eastbourne’s working class history.

Eastbourne was designed and developed by its landowners from the 1850s, built as a new resort for the rich thus greatly expanding the population from less than 4,000 in 1851 to almost 35,000 by 1891. Many of the higher echelons of society would arrive from London to take up residence for the summer, bringing along their servants of course. Many of those grand houses, built for the elites and the Lords and Ladies, have since been converted into flats.

Designed as a new resort built “for gentlemen by gentlemen”. The working classes of the town were kept hidden from the sight of our elite visitors (“don’t go east of the pier, dear”). And so too, much of our working-class history was kept hidden. This walk is one attempt to bring some of this important history back to life. We hope you enjoy.

Contents

- Starting at the Pier

- The Queens Hotel

- Engels in Eastbourne

- Bath Chair Ranks at The Pier

- Boats on the Beach – Engels’ Ashes and Eleanor Marx

- The Mackintosh Rebellion 1929

- The View Hotel

- Paul Robeson at The Winter Garden

- George Meek, the “Bath Chair” Man

- Western Lawns, Looking Towards Beachy Head

- Epilogue

Starting at The Pier

“Don’t go east of the Pier, dear.”

We are not going east of the pier today, but there is some fabulous history that we urge you to check out. There are many information boards around the area, and you can also download a dedicated heritage trail.

The Queens Hotel

Looking east, you will see the Queens Hotel. Opening in 1880, it was the last of the grand hotels to be built in the town. It is thought it was deliberately positioned to provide a visual marker of the end of the Grand Parade to the west. The rich visitors to Eastbourne were warned, “don’t go east of the pier, dear”. This was where the working classes lived. The conditions they lived in were deplorable. Poverty and disease and all else associated with oppression. There is a whole lot of radical history I could dedicate to this alone, but for now, I will reference that Eastbourne was not built with workers in mind. It was an afterthought almost that they would need to be accommodated; and this only as it became apparent that the servants of the elite classes (that Eastbourne was built for) would not be able to service all their needs.

There were “special tours” set up for the more curious amongst the upper-class visitors. A bit like the Bedlam Tours when elite visitors were shown around Bethlem Hospital, gawping in horror at the inmates as some sort of macabre entertainment. Image the indignity of this. Anyway. Let’s continue.

To the east of the Queens Hotel there were smaller hotels and boarding houses built largely between 1790 and 1840. There was no road along the seafront on this side of the pier. When he could not get rooms at Astor House, Engels stayed in one of these smaller hotels, namely Regency Villa:

“Tomorrow, Louise (divorced wife of Karl Kautsky, famous German Social-Democrat) and I are going for a week to Eastbourne (address as before, 28 Marine Parade) as I need to regain a little strength before my journey to Germany”. (Letter to Lafargue, Marx’s son-in-law, 20th July 1893).

27 and 28 Marine Parade are Grade II listed and stand on the site of an earlier building where the “Society of the People Called Methodists” was founded in 1803. The present buildings were built in 1840.

Directions: With the Pier behind you, look inland.

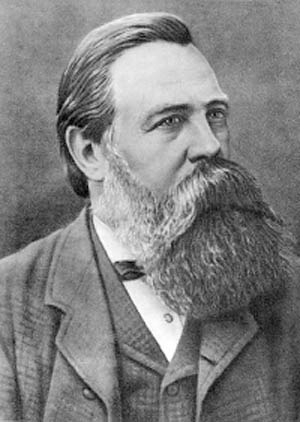

Engels in Eastbourne – Afton Hotel, 4 Cavendish Place, formerly Astor House

Built in 1850, Cavendish Place was one of the first streets to be built as part of the seventh Duke of Devonshire’s grand plan for the town.

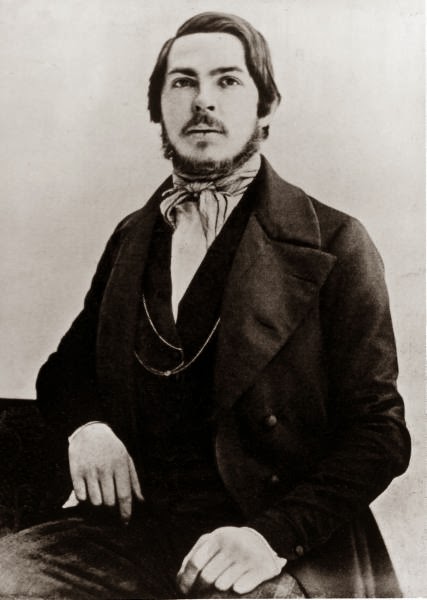

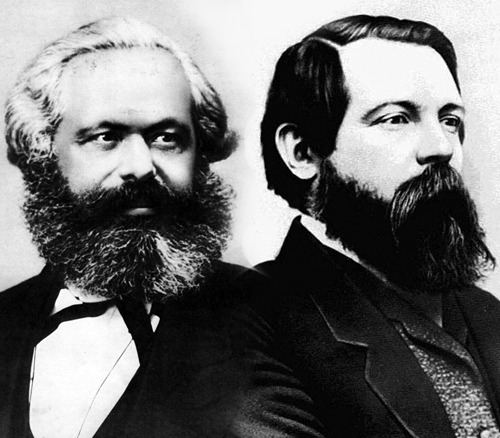

During the last 15 years or so of his life, Engels adopted Eastbourne as his favourite “go to” English seaside town. He was so fond of Eastbourne that whenever he had time to spare, he would hurry down, usually accompanied by a member of Marx’s family and/or close friends.

Engels regularly visited Eastbourne in the summer and sometimes other months, particularly after he took early retirement from the family business. He often stayed at Astor House, i.e. here, where the Afton Hotel now stands. (“…Near to the promenade and opposite the pier” – Letter to Laura Lafargue, second daughter of Marx, dated 19th August 1883).

Engels’ favourite walk (as it is for many of us in Eastbourne today) was along the seafront and over the downs to Beachy Head.

On 18th March 1893, Engels wrote to Sorge that he had spent two weeks in Eastbourne and “had splendid weather”, coming back “very refreshed”.1 As this letter suggests, it is most likely that Engels’ time in Eastbourne was his down time, for relaxation. But you never know, after Marx’s death on 14th March 1883, Engels may have worked at this address on the completion of volumes 2 and 3 of Das Kapital. (Long shot here!)

As Engels became sick with throat cancer, he sought the peace of Eastbourne more frequently. It was on his doctor’s orders that he stayed at 4 Cavendish Place during the last weeks of his life. He wrote his last letter from this address dated 23rd July 1895, addressed to Laura Lafargue. The letter ended, “I do not have the strength to write long letters, so keep well”. The next day he returned to London and died on August 5th, having added to his will a codicil that his ashes be scattered in the sea off Beachy Head.

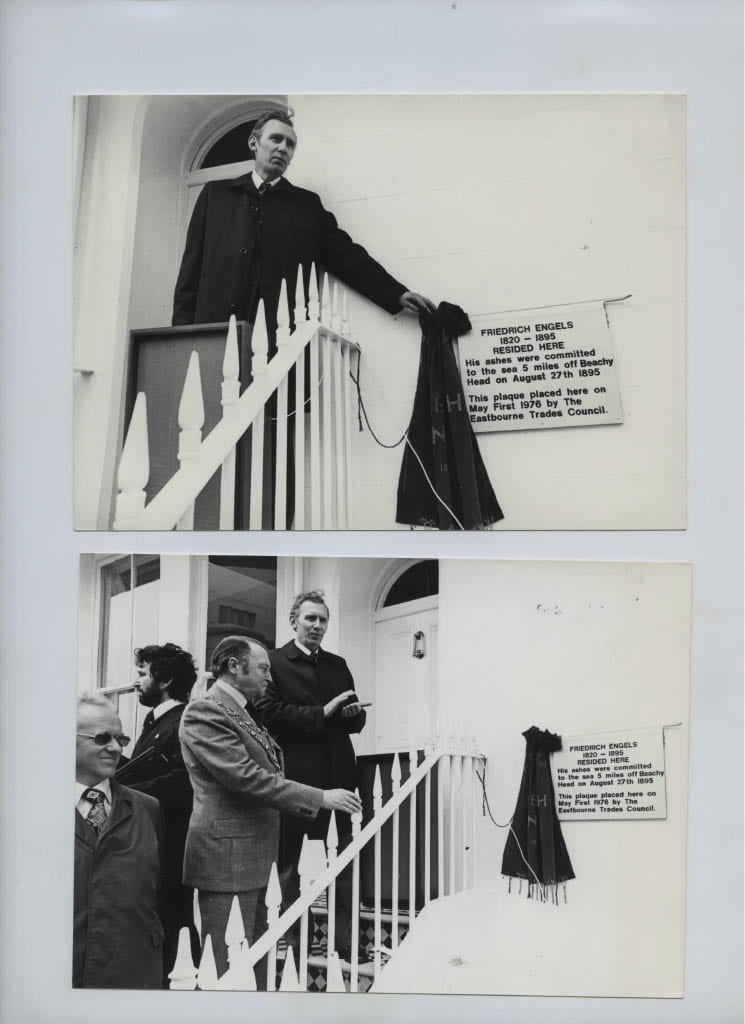

The 1976 Engels Plaque at 4 Cavendish Place

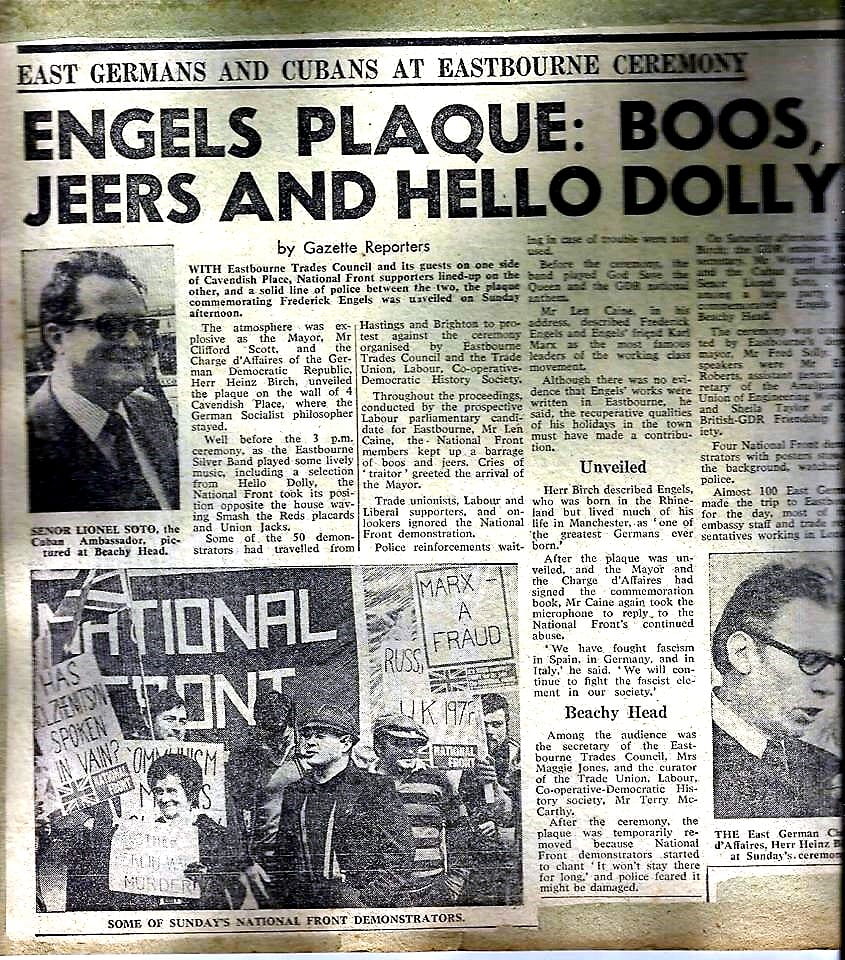

On May Day 1976 an Engels plaque was unveiled here at 4 Cavendish Place. This occasion was celebrated with the brass band first playing at the bandstand then marching down to Cavendish Place, where they played extracts from “Hello Dolly” before the unveiling at 3pm. The unveiling was attended by: Mayor Clifford Scott; the Cuban Ambassador, Lionel Sotto; Len Caine, who was the Labour Party prospective parliamentary candidate for the 1974 and 1979 elections (he was a prominent trade unionist in the town); and finally, and most importantly, the German Democratic Republic Charge d’Affaires, Herr Heinz Birch, who did the actual unveiling. Many dignitaries and visitors from both the German Democratic Republic and the Cuban embassies came to town for the ceremony, along with their families and friends.

Lionel Sotto, the Cuban Ambassador, had been imprisoned during the dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, released in 1959. He held positions within the Communist Party of Cuba and the Cuban Government.

Locals complained about the number of embassy cars parked on double yellow lines. The fines were not paid as diplomatic immunity was claimed. This annoyed some locals even more. I am also told the after-party in the basement of Astor House was a fine affair.

The Conservative and Liberal politicians in Eastbourne were unhappy about the Cubans and the Communist Party coming to town. Remember, this was before the fall of the Berlin Wall in the days of the Cold War. But the plans for who would do the unveiling and who would be invited had already been settled by members of the Communist Party (associated with the National Museum of Labour History in Limehouse – opened by Harold Wilson in 1975), before Eastbourne Trade Council was ever approached. So, the town was presented with a fait accompli, and they went along with it despite their reservations. (“Build it and the people will come”). And perhaps there was good cause for some degree of reservation considering what happened next.

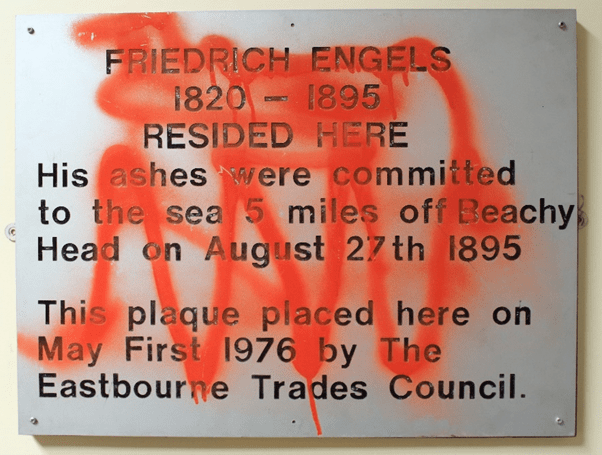

There was quite a crowd for the unveiling ceremony. But also present were a large group of members of the National Front (“from Brighton and Hastings”, according to the local newspaper report). They came to demonstrate. They were kept separated from the unveiling by a line of police. Their threats to damage the plaque were taken seriously and the plaque was taken down for the night. In fact, the plaque did not remain in place for long. Due to the owner’s concerns over the ongoing threats of criminal damage, it was only up for about 6 months. The plaque is currently in the archives of the Pump House People’s Museum in Manchester, complete with red paint vandalism. So, we have unfinished business with the fascists here in Eastbourne. The good people of Lewisham may have seen off the National Front at the Battle of Lewisham, 1977, but they got the better of us. We must put this right. We must get the plaque re-installed.2 3

For a full account of the story of the Engels plaque and plenty more it is worth visiting Engels in Eastbourne.

Directions: Look westwards from the Pier.

The Bath Chair Ranks at The Pier – beside the Carpet of Flowers

More on George Meek, the “bath chair” man later.

Boats on the Beach – Engels’ ashes and Eleanor Marx

Before the formation of the seafront, the beach directly east of the pier was the loading point of the early coal barges. A little further along is where the fishermen beached their vessels. Gradually, some of the vessels were turned to use for tourism. It is likely that the boat that took Engels’s ashes out to sea was hired from east of the pier. And so, on 27th August 1895, on a very stormy day, four set off in a boat carrying the urn containing Friedrich Engels’ ashes. The four were Eleanor

The View Hotel/UnitMarx (the youngest daughter of Karl Marx) and her ‘cad’ partner Edward Aveling, Eduard Bernstein and Frederick Lessner. According to the wording on the 1976 plaque, they dropped the ashes into the sea 5 miles off Beachy Head. However, this is unlikely to be correct, as in indicated in an article by Frederick Lessner. A moot point, you may think, but before coming across this article it had long baffled many of us as to how anyone could endure 5 miles in a small boat on a very stormy day – whereas hugging the coast for 2 miles up to Beachy Head and back would have been do-able?

Back to Eleanor Marx, to whom we simply must dedicate a few words. She was the youngest daughter of Karl Marx; she and her sisters Helen and Laura were often invited to join Engels in Eastbourne. Marx once said of his daughters, “Laura is like me, Eleanor IS me”. This tribute from Marx was well deserved. She was a determined political agitator, organiser and writer who threw herself into the struggles of her time against imperialism, racism, and sexism. She was a champion of the oppressed. She had a resolute recognition of the importance of workers’ unity. Whilst Eleanor supported the women’s movement’s call for reforms (e.g. women’s suffrage, higher education for women and so on) she was a revolutionary socialist. She contributed to a Marxist understanding of woman’s oppression with class being central to women’s liberation. She believed that working women’s struggles had more to do with working men than the middle-class leaders of the woman’s rights movement.

Directions: Proceed along the promenade west towards Beachy Head (clearly visible from all along the seafront). Stop before the bandstand and look out to sea.

The Mackintosh Rebellion 1929

It was a long hot summer in 1929 and there was a late heatwave. The 1920s saw the seaside opening up to the working classes thanks to improved working conditions, paid holidays, and an affordable railway network. No longer was Eastbourne the sole preserve of the elites. The heyday of bathing carriages and servants was drawing to an end. Many resorts had already done away with imposing charges and only allowing those who hired a bathing carriage and corporation towel to enjoy sea bathing. The working classes no longer needed to keep to paddling with their hankies on their heads as they could not afford the charges, which included 8p per half hour for the carriage and 2 pence for a towel, plus tip. That was nearly a shilling a dip. For a family of 4 for a week, this amounted to over £1 or about £70 in today’s money! Instead, a new working-class bathing habit had arrived in the resorts – the mackintosh bathers. Visitors would arrive on the beach straight from their guest houses already clad in their bathing gear, covered by their long mackintoshes. By 1929 most resorts were resigned to the changes and had abandoned the charges, but Eastbourne was not having it. Those in charge resisted the vulgarity of free bathing. Eastbourne was determined to hang on to its “elite resort” status for as long as possible. Council officials patrolled the pebbles issuing stern warnings about the bylaws. Eastbourne could not be doing with the common people. And besides, 1928 had seen £5,300 profit for the Corporation – that is £300,000 in today’s money, double the profit of 1927. So, which was it to be? Profits or people? Time for a showdown.

13th September 1929 was the day class war came to Eastbourne. The “Bolsheviks of bathing” had their sights set on action. An act of civil disobedience saw 150 mackintoshed men and women march their way to the shore, with puzzled onlookers not knowing what to make of it. The beach patrollers rallied upon the protesters, demanding their names and addresses so that official letters of reprimand could be correctly executed. The ultimate sanction.

The Eastbourne Mackintosh Rebellion hit national headline news for a full 5 days. The country was on the side of the people. The bathing carriages were described as smelly, dirty, and damp.

One reporter asserted “the name of Eastbourne should stink in the nostrils of holiday makers until Eastbourne’s governors are changed!”

The response? “We do not mean to be vindictive, but we will not have our authority flouted!”

By 1932 almost all charges across the country had been abandoned. The end of an era. Even for Eastbourne, that oh so exclusive town “built for gentlemen by gentlemen”.

‘Coastal Stories’ by Charlie Connelly

For more about The Mackintosh Rebellion listen to the ‘Coastal Stories’ Podcast brought to you by Charlie Connelly, bestselling author of ‘Attention All Shipping’.

Directions: Proceed westward along the promenade. Keep an eye on the roadside hotels and buildings. On the other side of the bandstand, stop when you see the tall standalone, dark glassed, 1970s-style hotel on the seafront (The View Hotel). Make your way to the roadside so you can get a good look. You may even want to stop off for coffee or for lunch here and look at the photographs of some of our Trade Union history on the mezzanine level.

The View Hotel (formerly the Transport and General Workers’ Union Convalescence Hotel and Conference Centre)

The View Hotel is distinct, the concept of a British architect. News was put about that the design was based on the Communist Party Headquarters. But this was a rumour started by some of the locals who were not impressepaneld and were a bit suspicious, no doubt wondering what was going on behind that plentiful dark glass. (Look out, look out, shady communists about!)

A main theme of the design was that all the materials in the hotel’s build and furnishing would be of British origin, thus supporting British industry and workers. Hence the use of ceramics from the Staffordshire Potteries; aluminium windows and framing by British Alcan; and the much maligned but beautiful heather slate on the frontage. The slate quarry was saved from closure by the size of the order, with slate used extensively on the ground floor and first floor both inside and out. Sadly, much of this has been covered over as part of the “modernisation”. Even the cutlery was specified as being of British manufacture despite its higher cost.

In September 1974, the first stone was laid by Jack Jones for the TGWU’s new purpose-built convalescence holiday hotel and educational centre at Eastbourne. The Eastbourne Centre was then opened by Jack Jones in October 1976. Now called The View Hotel, the Centre was used as a workers’ recuperation and holiday centre, and a Conference Centre for the union. The hotel is still owned by Unite the Union. The mezzanine level at The View shows some of the hotel’s union history.

Jack Jones left school at 14 and after a few jobs joined his father as a Liverpool Docker. He became an active member of the Transport and General Workers’ Union, and later served as General Secretary of this union from 1968 until 1978. He was a great trade unionist, having been converted to socialism by reading The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists. Jack once explained how that book “was passed from hand to hand among people in the Labour movement and had a remarkable effect on our thinking”.

At the time of its creation in 1922, the Transport and General Workers’ Union (TGWU) was the largest and most ambitious amalgamation brought about within trade unionism. Later, following various talks between unions, a merger with Amicus was agreed and Unite the Union was created in 2007.

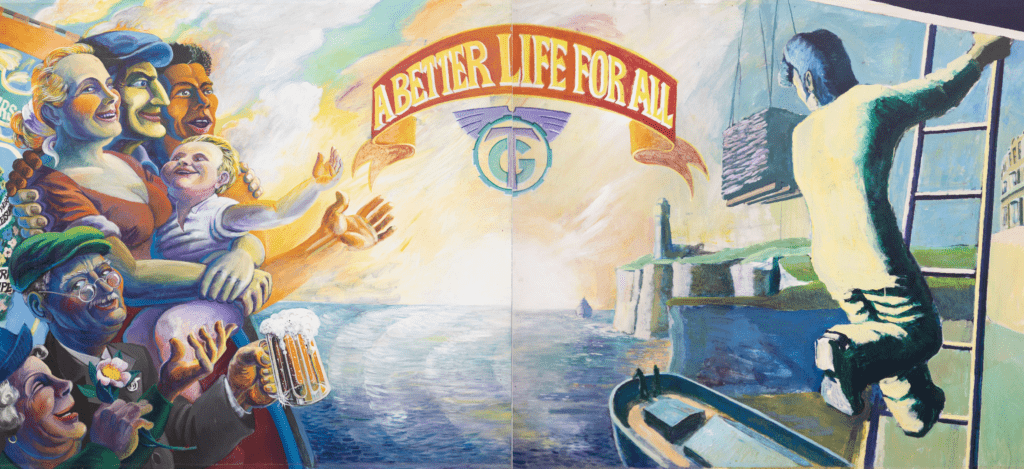

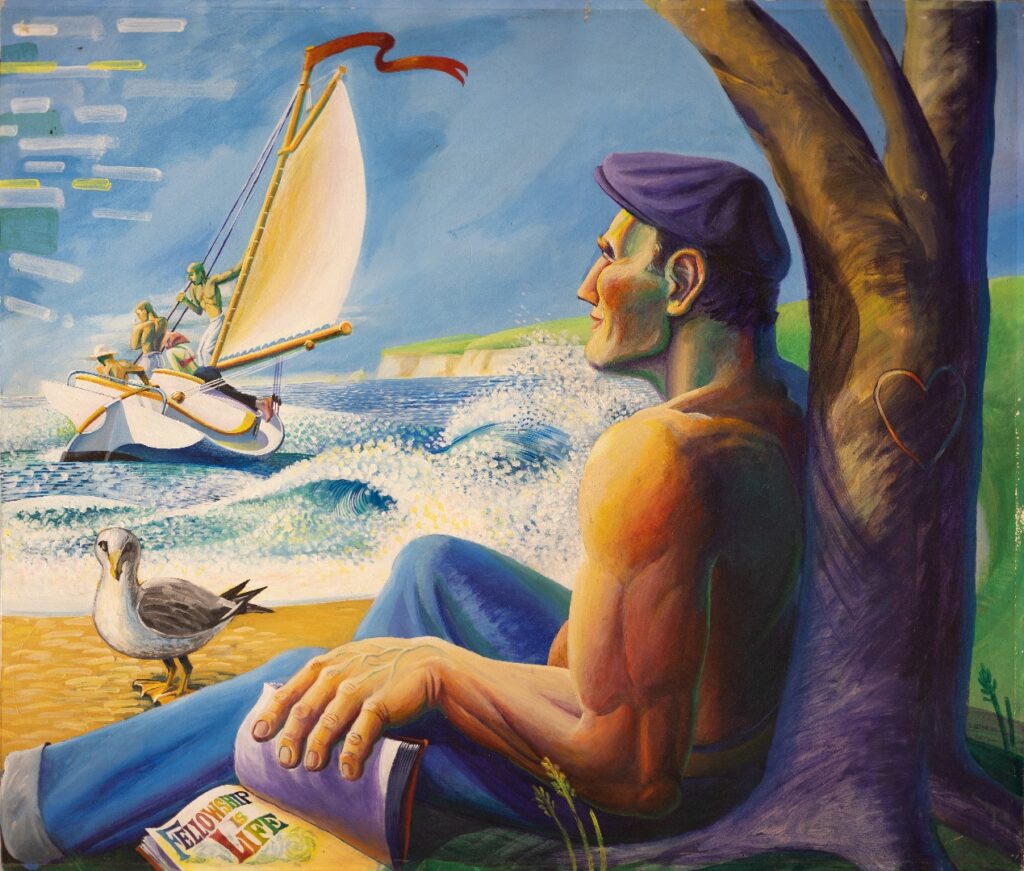

The International Workers’ Mural

In the dining room of the Centre there used to be Eastbourne’s International Workers’ Mural. It was a full sized, very colourful, and was created by the Art Workers Co-operative – Michael ‘Mick’ Jones, Christopher Robinson, and Simon Barber. Mick Jones was the son of Jack Jones, a trade unionist. The mural is an artistic tribute to international trade unionism and the importance of solidarity amongst workers. For example, part of the mural illustrates “the union’s struggle through depression and war from which emerges a victorious procession with banners of the amalgamated unions. Support for the Spanish Republic in the 1930s is shown by the inclusion of the graffiti, ‘SOLIDARITY WITH SPAIN’.”

The mural was dismantled during the renovation of The View Hotel. It is stored safely in boxes in Birmingham. The plan was for it to be reassembled in the National Unite Conference Centre and Hotel (Birmingham). But it is difficult to display a mural in a building with so much glass. So, for now, in boxes it remains!

Unite Community Eastbourne have been in discussion with the Manager of The View and the Director of The Towner art gallery working on ensuring the story of the mural is not lost from Eastbourne history. Work is in progress for a pull-out brochure showing the mural in all its colourful glory. Also, for an exhibition of the mural somewhere in town. The Campaign to bring the mural back to Eastbourne has been a difficult one and is very much ongoing. The aim is for it to be permanently archived safely in Eastbourne and for regular public viewing to be arranged. The quest to find a permanent site in Eastbourne has been marked with disappointment and frustration. 89 foot long of permanent space does not come easy. The mural contains many references to Eastbourne and was likely inspired by our Sussex coastline. Certainly, one section of the mural shows the Beachy Head lighthouse. Another panel contains a bus with Eastbourne as the destination. This mural belongs in Eastbourne. Not in boxes in Birmingham!

Directions: Proceed westwards a little way. Turn right into Carlisle Road and proceed to the end. (You may wish to pop into Favoloso for an ice cream treat – many varieties.) The Winter Garden is opposite the end of Carlisle Road.

Paul Robeson at The Winter Garden

We simply cannot do justice to Paul Robeson’s greatness here. Suffice to say he was magnificently gifted and an incredibly principled, influential civil rights activist and internationalist who spoke out for black and working-class people at every opportunity. Ahead of his time, he was not deterred by the McCarthyism he was subjected to in the USA. This included having his passport confiscated for 8 years and not being allowed to travel to places he didn’t need a passport for (i.e. Canada – a law was passed especially for this purpose). There is a campaign for Paul Robeson’s time in Eastbourne to be commemorated in a truly fitting way e.g. A Paul Robeson Room at the Winter Garden. We will keep you posted via the Engels in Eastbourne Campaign. In the meantime, please enjoy a selection of reviews of his performances in Eastbourne.

After his success in the stage production of Showboat in 1928 in London, [Paul Robeson] undertook ‘his first provincial tour… he gave a concert in Blackpool… he also sang in Birmingham, Torquay, Brighton, Eastbourne, Folkestone, Margate, Hastings, Southsea, and Douglas…. Robeson returned to perform in the town on 11 August 1935, possibly, again in 1936, and again on 7 August 1938 in the Floral Hall at the Winter Garden in Eastbourne. As the Eastbourne Gazette reported on 10 August 1938, there were ‘remarkable scenes at Winter Garden’ as an audience of 1,800 were ‘bewitched’ by ‘the magic’ of ‘that master of song’ Paul Robeson, with ‘hundreds’ being turned panelaway, unable to get seats to listen. Overall, Robeson performed in Eastbourne at least 9 if not 10 times.

Directions: With the Winter Gardens at your back, you will see Wilmington Square on the opposite side of the road to the right.

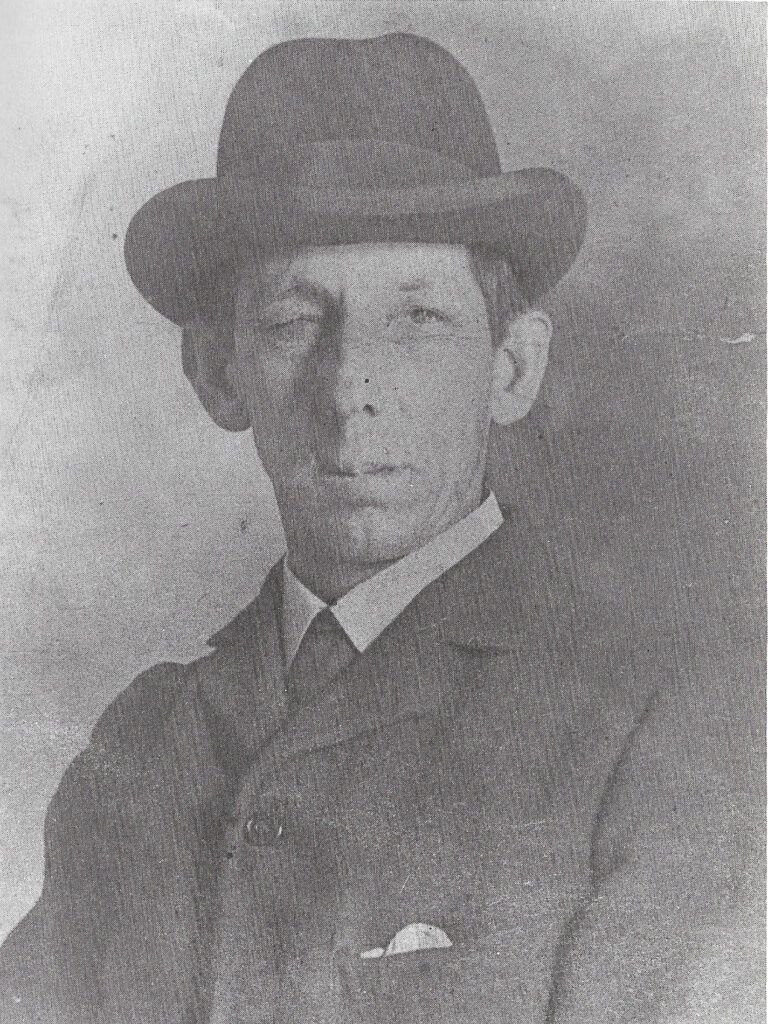

George Meek a “Bath Chair” Man – Wilmington Square

George Meek (1868–1921) was a kind of real life, Eastbourne version of Frank Owen, the working-class hero of The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists written by Robert Tressell from 1906 to 1910 in Hastings, just 19 miles along the coast east of Eastbourne. George Meek was a key figure in encouraging socialist ideas in the town. He was one of these bath chairmen in our town, a poorly paid, insecure job, reliant on the tourist trade and good weather. He lived on the edge of poverty throughout his life. His two younger brothers, Joe and Arthur, were temporarily sent to the workhouse at times when his mother had difficulty care for them due to poverty.

During Meek’s lifetime, there were very few accounts of working-class life in Britain written by working class people. There were a number of factual surveys (including, of course, Engels’ Condition of the Working Class in Britain, published in 1845 There were also several personal accounts, e.g. Robert Tressell’s novel, mentioned above, and Jack London’s People of the Abyss. Meek was encouraged and supported to write about his own experience under the mentorship of H.G. Wells, whom he had met during one of his “walk abouts” looking for work. Meek’s autobiography4 was a great achievement considering he only received brief and inconsistent schooling. He was alone amongst all these writers in that he was from a working-class background and remained in poor circumstances throughout his life.

These extracts give a flavour of what life was like for a bath chair man:

If you would know the horror of black despair, go out with a bath chair day after day, with the chair-owner or landlord worrying you for rent, food needed at home, and get nothing. Stare till your eyes ache; pray with aching heart to a God whom you ultimately curse for his deafness. And this not for a few weeks, but year after year.

George Meek, quoted by Bill Coxall and Clive Griggs in their biography of him5

Among the chair-men I have known since I first began to work at the calling seven have gone mad, many have taken to drink, others have died in the workhouse or are still there. The work demoralises everyone in some way. It sets man against man. Some will do the meanest things to get work away from others. For instance, men have gone to my customers and told them that I could not see, or that I was a Socialist, or that I drink. It is quite a common thing for me to get passengers and then suddenly lose them.

George Meek, in his autobiography

On the corner of the square “anonymous” pillar box (anonymous because it does not carry the VR cipher). It is on this spot where George Meek was granted a rare act of charity from one of our elite visitors.

On one Sunday at the turn of the century Meek had been waiting on the corner of Wilmington Square for twelve hours from 8am onwards without a single fare. He was just moving off home when a gentleman hailed him and not as it turned out for the hire of his chair but merely to ask him for a light. “Very busy?” he asked Meek whereupon the latter told him how he had spent the day. “That’s hard lines, here’s half a crown”, and on learning that Meek had a family he added, “Here’s another five shillings.”

Bill Coxall and Clive Griggs in their biography of George Meek

Bear in mind here that George Meek had to pay rent for the bath chair. No fare equalled debt to the rentier classes.

Directions: Proceed westwards to the crossing. Cross over the seafront to The Western Lawns. Walk through to the seafront.

10. Western Lawns, Looking Towards Beachy Head

Engels so loved Eastbourne that one of his final acts was to write a codicil into his will to ensure his ashes were scattered off Beachy Head. It is worth taking a hike up to Beachy Head, a real beauty spot that marks the end of the South Downs Way. We are lucky that the area is so unspoilt, but it could have been very different. Twice in our history, Beachy Head has been in danger of falling prey to developers. PEOPLE POWER prevented this from happening on both occasions. In 1926 a “mysterious group of property developers” wanted to build a new town on the Seven Sisters cliffs, where Beachy Head sits. Opposing them was a group of early environmentalists, including poet Rudyard Kipling. There followed the Eastbourne Corporation Act 1926 and in 1929 the compulsory purchase of 4,100 acres was completed. The Corporation became the owners of the whole of Beachy Head, and the 4,100 acres northwards and westwards of it, at a cost to the town of nearly £100,000 (an absolute bargain!).

At the 1926 Parliamentary Select Committee, the Mayor of Eastbourne, Charles Knight, was asked: “Is it the deliberate intention of the Corporation, in promoting this clause, to secure the public the free and open use of the Downs in perpetuity?”

The mayor replied: “Absolutely.”

90 years later, Eastbourne Borough Council tried to backtrack on this assertion, when early in 2016 they decided to sell the four farms in the South Downs National Park, without most residents being aware.6

But the people were having none of it. The Keep Our Downs Public Campaign was set up, launching a cross-party fight for a reversal of this decision. We won. The decision was abandoned, and our much-loved downland remains in public ownership. And long may it last. It may have not been a revolution of the Marx and Engels sort, but we were proud of our efforts, and I am fairly sure Engels would have been delighted, too.

Power to the people, in Eastbourne, no less!

Every generation must fight the same battles again and again. There’s no final victory and there’s no final defeat and therefore a little bit of history may help.

Tony Benn

- Tristram Hunt, The Frock-Coated Communist, Penguin 2010. ↩︎

- From the file of the Eastbourne Gazette. May 1910 ↩︎

- Can We Have Our Engels Plaque Back Please? – article in the Eastbourne Voice January 2018 edition. ↩︎

- George Meek, Bath Chair Man – MEEK, GEORGE, 1868-1921 by himself. Hard Press Classics Series. ↩︎

- George Meek. Labouring Man: Protégé of H.G.Wells by Bill Coxall and Clive Griggs. Page 102. ↩︎

- Eastbourne Herald: Group fights council’s plans to sell off Downland, 10th November 2016. ↩︎